From Dues to Don’ts: How a Danish Toll Still Shapes Maritime Analysis Today

With the ongoing discussion in the media and among analysts about dark fleet vessels and UNCLOS, I thought it would be interesting to discuss a specific event in maritime history that has had a long-lasting impact on our current maritime laws: Øresundstolden or the Øresund Sound Dues.

You may have heard the terms “freedom of navigation” or “freedom of the seas” being thrown around when a Russian tanker or a Chinese fishing vessel is suspected of sanctions evasion or grey-war tactics, but where does it come from?

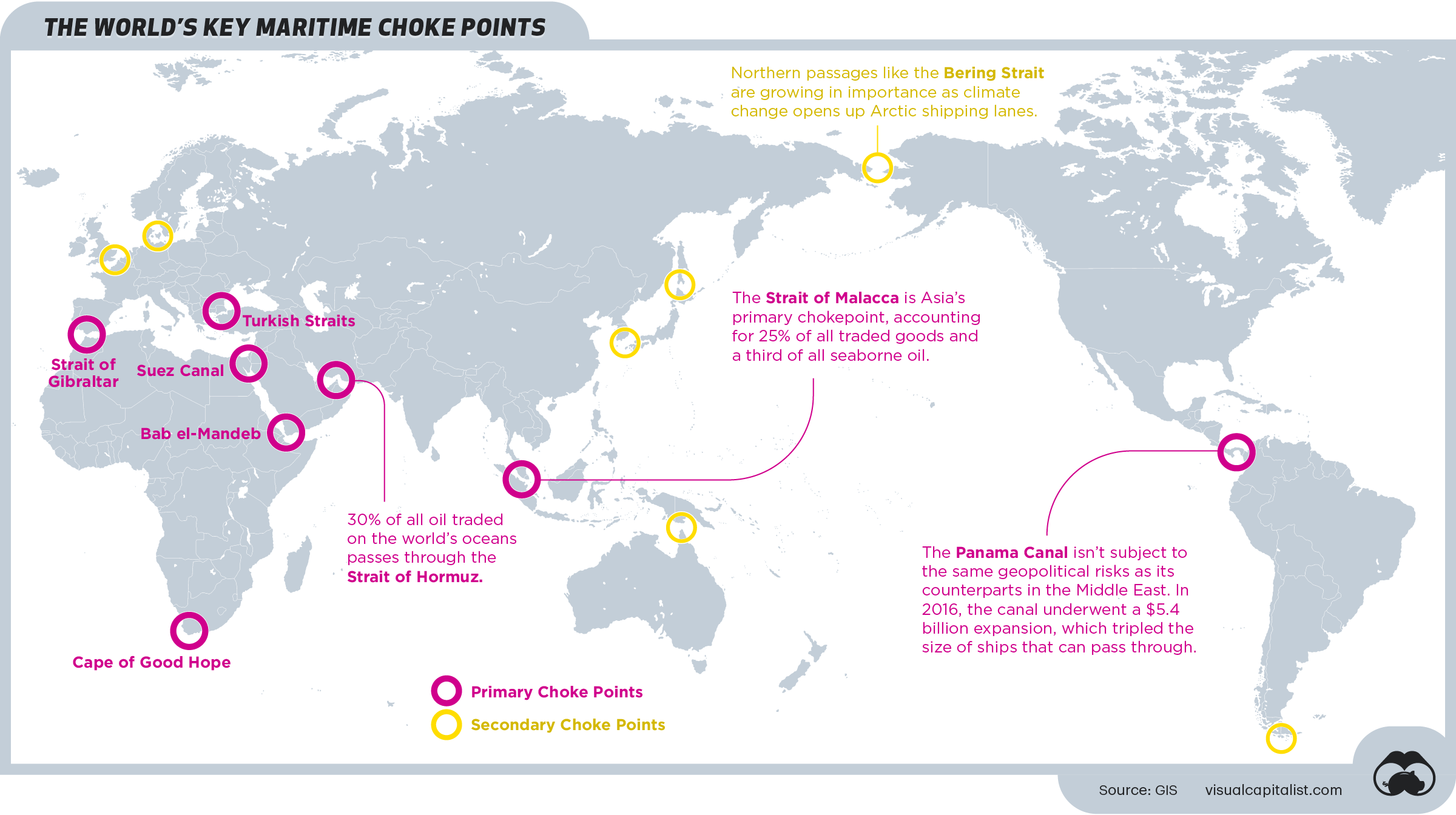

The answer may stem from a small strip of water running between Denmark and Sweden. For centuries, each ship entering or leaving the Baltic paid a passage fee at Øresund, turning a geopolitical chokepoint into both an engine of revenue and a tool of political pressure, a dynamic still reflected in today’s laws on who controls what at sea.

From this medieval toll grew a web of treaties and laws that still shape how we understand “free passage” and, moreso how we should read maritime data and narratives in modern OSINT work.

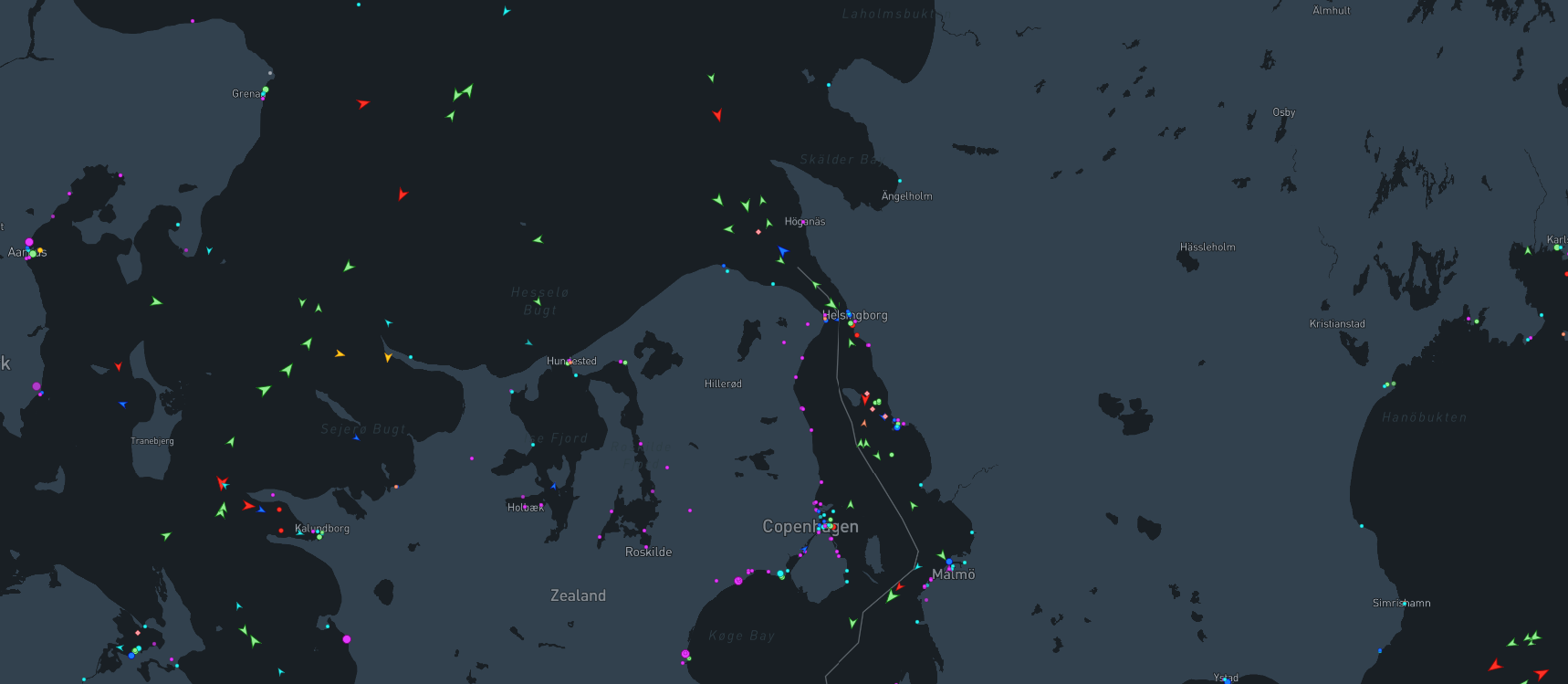

The Øresund Strait viewed on Marine Traffic

A Toll that Built a Kingdom

In 15th century Denmark, King Erik of Pomerania, ruler of the Kalmar Union (Denmark/Norway/Sweden) realized that they could tax an entire sea through a single strait. The Øresund was the main artery connecting the North Sea and the Baltic and the gateway for transporting grain, timber, tar, metals, and fish between Russia, Sweden, Poland, Germany, and Amsterdam. At the time, Denmark controlled both sides of this narrow passage and they fortified it heavily. Each ship that entered or left the Baltic was required by the crown to stop under threat of canon fire at the royal fortress at Helsingør toll house (the medieval Krogen, later rebuilt as Kronborg), and pay the sound dues before continuing through the strait.

Over time, the dues changed from set per ship fees to ad valorem rates, meaning they pay about 1-2% of the total declared cargo, changing Øresund into an ongoing pipeline of money rather than a one-off money grab.

Krogen Fortress

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the Sound Dues were raking in nearly half of Denmark’s income, which in turn completely funded (along with many other projects in Copenhagen and the Navy) the construction of the old Krogen fortress into what is now: the Shakespearean Kronborg castle. The crown built a customs office with clerks that routinely interrogated captains, checked cargo lists, and meticulously logged transit, creating a ship-by-ship record of Baltic trade at the time.

Then Politics and big personalities began creeping in. Mother Sigbrit, the widow of a Dutch merchant and advisor to King Christian II (who inherited the throne in 1513), was given responsibility for the royal finances, including the Sound dues. Sigbrit was strict about how money was handled, which made traders nervous because they saw it as a money grab. Because they hated the new rules, merchants began to use evasive tactics to hide their cargo and avoid paying the full fees by gaming the system. In turn, the crown responded by increasing cargo checks, cross-checking routes and manifests, and generally making it harder for merchants to sneak through paying less. The situation turned into a cat-and-mouse game.

In the Second Northern War (1655–1660), Denmark ceded roughly 1/3 of its territory to Sweden (Treaty of Roskilde 1658), including the eastern shore of Øresund, which meant Denmark no longer controlled both sides of the strait. This could have been devastating for Denmark, but in a weird turn of events, shipowners continued to pay the Sound Dues out of habit. A writer from the time period is quoted as saying:

“God alone knows why they still paid up, after we no longer controlled the sound.”

Kronborg Castle and inspiration for Shakespeare’s Hamlet (Elsinor)

Buying Free Passage

By the 19th century, people were completely fed up with paying a toll to travel through the sound. The US and Britain, among other countries, pushed to end the Sound Dues rather than continuing the back-and-forth over rates and exemptions. Beyond the Dues themselves, the system in place for checking shipments and garnering certificates left merchants waiting for days in Elsinor, racking up fees that would even exceed the Dues. As foreign shipping began choking trade to Copenhagen, Denmark revised their stance and accepted a treaty to guarantee free passage for merchant shipping through the Danish Straits as long as they retain sovereignty, forts, and navigation rules.

In the 1857 Copenhagen convention, Denmark agreed to end the Dues in exchange for 33.5 rigsdaler and perpetual free passage. This payment was split between Britain, Russia, and the US (who paid roughly 393,000 dollars in 1857 and roughly 14–15 million USD in 2025). This led to a situation where the sound was no longer Danish coastal water, nor was it fully open water, but rather operated under special rules.

From Dues to Don’ts

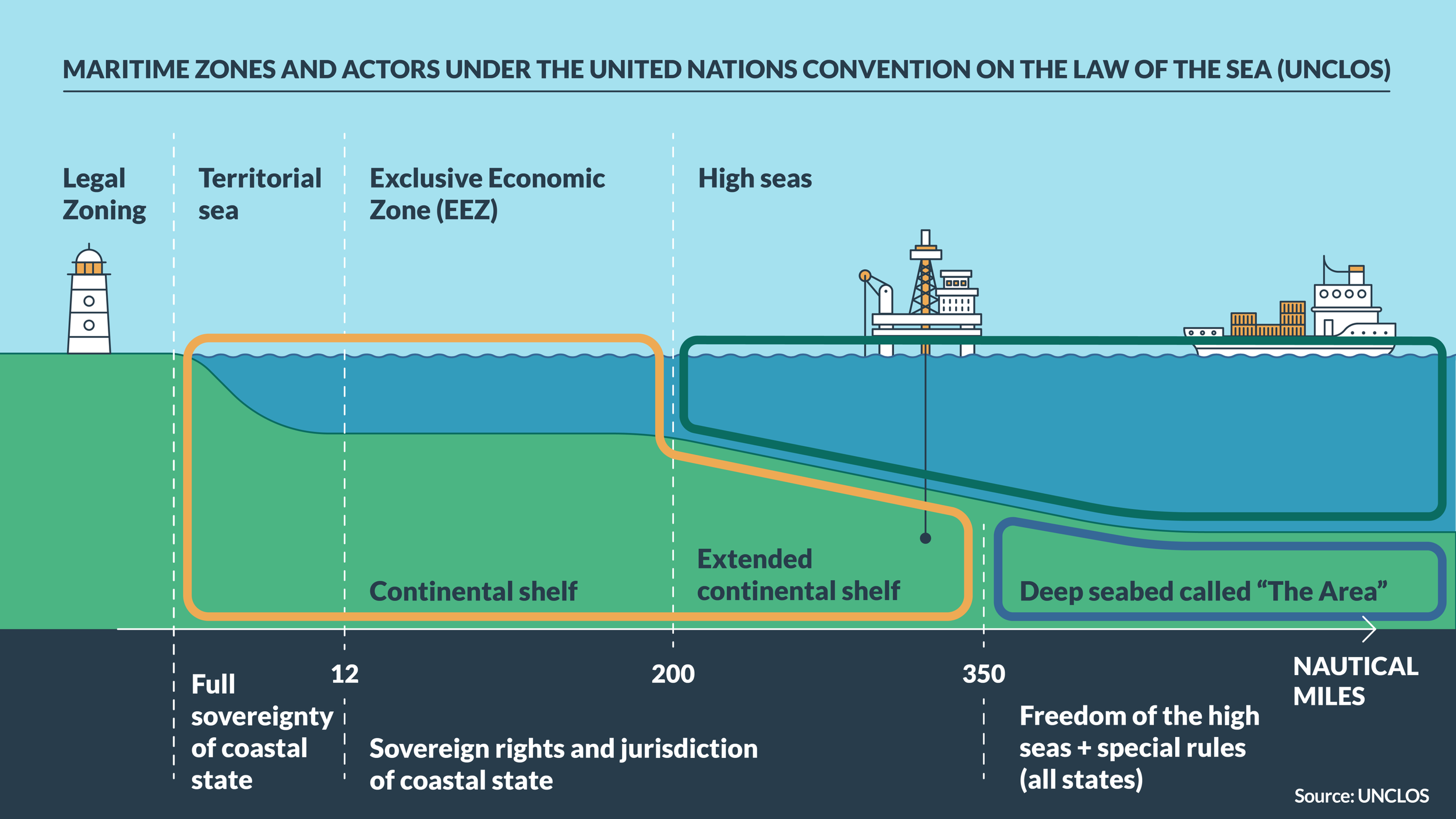

The problem with the Copenhagen Treaty, especially in narrow straits like the Øresund, is that the entire thing ends up falling inside “national waters.” If it’s considered national waters, do warships and submarines get free passage through the area, or can the nation say no? This ruffled feathers with Naval powers, and they argued dring negotiations for the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) that they require a transit passage (basically the free right to pass from one end to the other) in any major waterways. Coastal states like Denmark fired back that the Copenhagen Treaty prevented the removal of their rights to determine what happens in their waters.

This argument brought about a list of don’ts, including:

Submarines must transit at the surface with their flag visible

Warships can’t run exercises or intel collection during passage

Aircraft have no automatic right to cross overhead

UNCLOS eventually developed a global rulebook in 1994 that defines maritime zones and rules for special spaces like the Danish Straits.

UNCLOS Maritime Zones

Why This Matters for OSINT and Maritime Analysis

In modern maritime analysis and OSINT, all of this history is deeply embedded in the data. They go hand-in-hand because when you look at AIS tracks, port calls, and patterns, you are watching decisions and behaviors driven by centuries of wars, treaties, tolls, and legal battles at sea.

Chokepoints around the world

Applying this history to the current issue of shadow-fleet tankers begs the question: Does UNCLOS guarantee the right of free passage protect legitimate navigation, or does it also help sanctioned/illicit vessels slip through the cracks?

Within the Danish Straits, UNCLOS and the Copenhagen Convention make it difficult for Denmark to stop these shadow-fleet tankers from passing through. Of course, they could enforce safety rules, but sanctions alone are most likely not enough to prevent passage.

On the flip side, the US (not a ratified party to UNCLOS), has been boarding and seizing suspected shadow-fleet tankers like Bella 1/Marinera (IMO: 9230880) in the open seas under sanctions laws. In the case of the Bella 1, it seems like the US is using stateless status, based on its reflagging as a catalyst for boarding under UNCLOS. It remains to be seen how this will all play out, but the fact remains that Straits like the Øresund, Malacca, or Taiwan are prime spaces for grey-zone behavior, combining heavy vessel traffic with ambiguous legalities.

Bella 1 from Marine Traffic

For us working in the maritime intelligence world, the Danish Sound Dues are an origin story for the way in which the sea is governed. It is a reminder that building an analytic picture requires historical context to be completely effective.

The history of the Danish Straits is still influencing maritime doctrine and analysis today.

To read more about the Sound Dues, check out The Danish Sound Dues and the Command of the Baltic: a Study of International Relations : Charles E. Hill, and The Sound Toll at Elsinore Politics, Shipping and the Collection of Duties 1429–1857 Edited by Ole Degn

Tak for at læse med!