Russia's Little Red Men: The Shadow Fleet Spies Nobody’s Looking For

Most maritime OSINT analysts I know focus on vessels as the key indicator for illicit activity. Digging into flag hopping, shell companies, ownership structures, and dark activity. Of course, this work matters because it feeds directly into detection and enforcement. We see this in reporting, such as when Kpler analyzed and identified 302 high-risk shadow-fleet vessels last October (52 were subsequently sanctioned) based on behavior and risk scoring. This methodology works, but we are forgetting a key aspect of shipping: the human layer, and Russia knows.

The Vessels Are the Cover Story

Analysts have gotten incredibly good at tracking shadow fleet vessel behavior, but we tend to focus less effort on asking who is on these ships and why. However, the true operations begin with people, and the same obfuscation techniques used to hide vessels might be designed to make the crew invisible and international laws unenforceable.

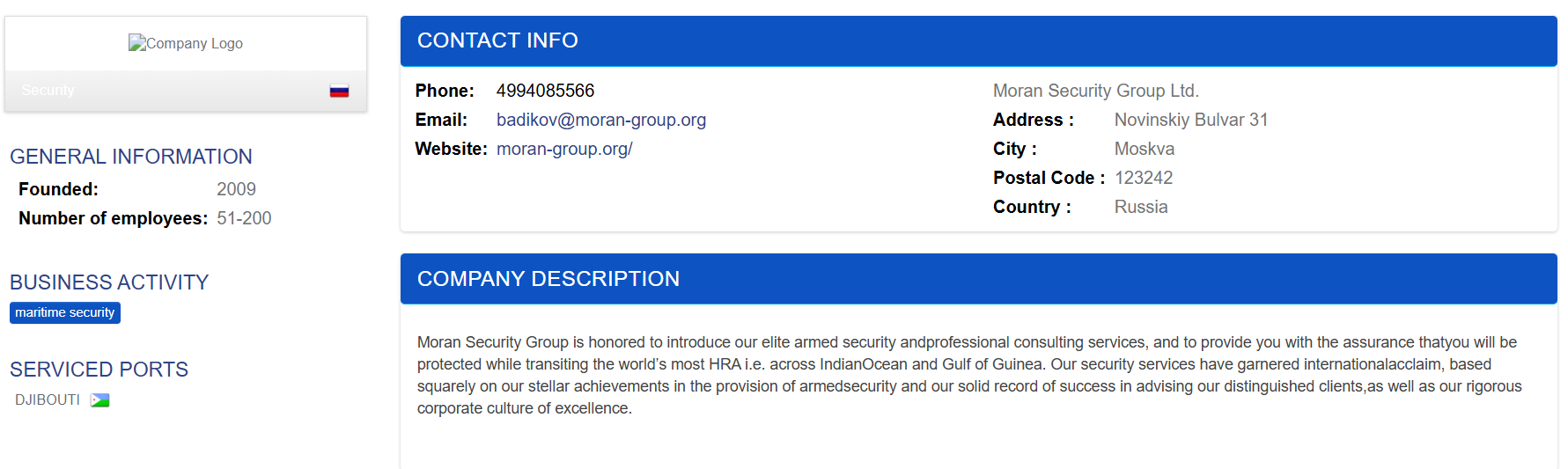

In December 2025, CNN documented how armed Russians with military and intelligence backgrounds were observed covertly boarding shadow fleet vessels. They were listed as “technicians,” but they were the only Russians on non-Russian crews. The men were employed by Moran Security Group, tied to Russia's intelligence services, military, and the Wagner Group.

Source: CNN

Moran is a private maritime security company (PMSC) offering elite armed security services while transiting the sea. They recruit "active or retired officers who have served in special forces units (GRU, airborne troops, naval commandos) and their President, Vyacheslav Kalashnikov, is a retired FSB lieutenant colonel. Unsurprisingly, the US Treasury sanctioned Moran in 2024.

Source: MarineTraffic

What They're Doing

Based on CNN's reporting, supported by foreign and Western intelligence alongside firsthand accounts, several behaviors were observed:

Monitoring of ship captains.

If dark fleet or shadow fleet captains aren’t Russian, PMSC groups like Moran are there to make sure the crew fulfills the goals of the Kremlin.

Photographing military installations.

Maritime surveillance is not new. For example, the Yantar, a vessel widely believed to be a Russian spy ship, is often accused of behaviors like directing lasers at military and mapping subsea cables. Dark and shadow fleet vessels routinely operate near NATO coastlines, which present an opportunity for photographing facilities, as confirmed by a Western intelligence source in the CNN article.

Potential aerial recon.

In September 2025, the tanker vessel Boracay (IMO: 9332810), reportedly with two Moran personnel onboard, was roughly 50 NM from Copenhagen when drones shut down the airport. While the ship was never confirmed to be responsible, it was investigated by the Danish Security Services.

The Eagle S Proved the Method Works

Source: Marine Traffic / RAIMO MAKINEN

The captain and officers of Russian-linked tanker Eagle S were charged by Finland for aggravated sabotage after the vessel severed the Estlink 2 cable in December 2024. Despite leaving drag marks on the seabed, having a damaged/missing anchor, and several risk markers and anomalous activity, the courts dismissed the case in October 2025 for Insufficient proof of intent.

Lloyd's List also reported that the Eagle S carried surveillance equipment used to monitor NATO frequencies, and sources report sensors being dropped in the English Channel. The Finnish police seized devices for analysis, but there was never any public confirmation. It does not seem far-fetched to think that Russia engineered this so that even if caught, international law struggles to enforce laws against them.

The Collection Gap

Typically, analysts use a mix of online databases, AIS tracking platforms, social media, and news reports to gain an understanding of the maritime domain. This process works pretty well for legitimate companies, stable crew lists with traceable employment histories. But when we are investigating vessels with constant identity manipulations, re-flagging, layers of shell companies, unlisted or hidden crew, it becomes a deliberately obfuscated mess. Even the CNN article mentions the Moran information coming from Ukrainian intelligence, not open sources.

There are detectable signals (Hired security, Russians within a non-Russian crew), but only if you have access to the crew manifests, which aren’t usually readily available in open source data. Furthermore, accessing this type of data for shadow fleet vessels proves to be a significantly different problem than looking at a container ship out of Canada.

The gap isn’t that OSINT and maritime analysts aren’t looking for crew lists; it’s that access to this data, alongside deliberate adversarial obfuscation, makes collection nearly impossible.

As it stands, we are only collecting on the ships, rarely the people.

So, What’s the Solution?

Well, there isn’t an easy solution. OSINT analysts (at least those without government sources) tend to struggle with HUMINT. But there are a few things we can try:

Maritime Job: employment history

Linkedin: vessel names in work history

Local News: arrests, crew changes, and emergencies will often be covered

Court Records: maritime incidents might name crew

Detained vessel reporting: Track crew names and cross-check against other vessels

Social Media: Crew members post photos and mention vessel names

Equasis: Look for inspection details with crew information

Shipping Agent Websites: Sometimes list vessels they service or crew changes

Google Dorks: Try search “IMO number” and “crew” or “captain

I can’t promise any of these will give you full and current crew manifests, but the bits and pieces over time can sometimes reveal a network. Finding vessels based on behaviors and patterns is working, but if we are only ever asking “where is the ship” and never asking “who is on the ship” we are missing a big chunk of the full picture.